The Vietnam and Military Art of

Ben M. Kennedy

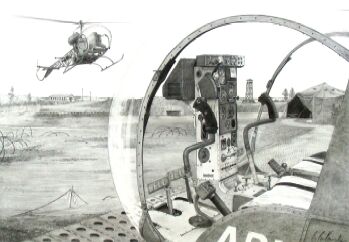

Dolphin Crewchief

and Military Artist

1969

|

|---|

About the Artist

A veteran of three tours in Vietnam, between 1968 and 1971, Ben Kennedy's passion for aviation, and the UH-1 Huey helicopter in particular, is well reflected in this collection of his artwork. His stories, poems, and other descriptions add to the overall sense that this is a personal history -- but not just his. It is a history of thousands of young men, some of whom did not live to remember it. During the war, the artist often traded a quick sketch of the day's mission for a Pepsi. Nowadays his pockets bulge with technical pens, but years ago pencils, ball-points, and even cigarette butts proved useful to his art. He drew or painted on wooden planks, paper napkins, and helicopter noses.

Below are representative paintings and drawings of Ben Kennedy. This "picture-book" of memories is not just of the 174th, but it tells the story of different helicopters and units, including specialized missions, combat assaults, shootdowns, search-and-rescues, and also includes many of the fixed-wing airplanes and jets with which the helicopters interacted. Mr. Kennedy's love for the technicality of these machines is evident in the detailed, realistic style of his presentation. The book that's represented here is now out of print, but is available from various online resale sources (just Google the title). All artwork, poems, and stories contained herein are copyrighted and not to be reproduced without Mr. Kennedy's permission.

|

|---|

"THE ASSAULT"

A Poemby Ben Kennedy

Night shadows retreat into the deepness of the eastern sea,

Dawn breaking and airmen wonder what shall come to be.

To the west, a forbidding mountain range, where all must fly,

In its thick and river laced valleys, know well, some shall die.

Warriors saunter about the aircraft, making ready to go,

Checking systems and ammo, in the ship so well they know.

Looking up into the cloudless, pale, paternal sky above,

Radios cackle and life hums thru the bird we've come to love.

Rotors clear and engine whines, as she struggles to her feet,

Four souls strapped into her bosom with destiny to meet.

Up and out of the revetment, by churning through the air,

Onto a makeshift, lumpy runway, aircraft assemble there.

Flight Lead gives the signal, "Pull Pitch," and the formation is on the go,

Skimming down the runway, and climbing, seeds of war to sow.

Compass set, in V's of three, thirty airplanes are in the sky,

Rush onward to the rendezvous where some will bleed and die.

Ponder yellow patches strewn over the ship winging by your side,

Consider their historical writings and what tales they seek to hide.

Panoramic rice paddies, hamlets and trails, slipping past below,

Across yonder mud brown river, cherry smoke marks where to go.

Dropping thru the heated atmosphere more soldiers now appear,

And back in the homeland, countermanders protest us and here.

Dipping down in the corridor, as all in thirty birds alight,

Rushing out of the NDP, ten men each to a bird, thirty in all,

Ponder the saga of young faces, and wonder of them who will fall.

Clattering across the cargo floor with weapons in tight-fisted clinch,

Soaked in perspiration for their courage notice not the human stench.

Flight Lead gives the signal and thirty aircraft now ready to go,

Skimming out along the corridor and climbing, seeds of war to sow.

Insipid grid cords and max ords pass thru our radios in the air,

Flight crews are busy working with ground troops, somber in stare.

Compass set, V's of three, with thirty aircraft in the sky,

Rush onward to the rendezvous where some will bleed and die.

Panoramic rice paddies, hamlets and trails, slipping past below,

Wonder about this enemy, who is he we regard as foe?

Whirling, whopping rotor blades beat out thunderings in the air,

A tiny FAC joins us with his sting still higher somewhere, there.

Over the staging area more aircraft now join our flight,

Swarm deep into the green denizen of this valley, so all an awesome sight.

Tin coffins over the landscape, upward of three hundred souls now loom,

Farther down into this region wild, where waits the impending doom.

Screaming thunder out of the heaven's jet fighters in a controlled fall.

Dumping snake and nape, red flashes burst bombs in nature's splendid hall.

Ground fire reports back the enemy's presence, as stricken war birds shudder,

Even men of stoutest, gallant heart, at this instant will experience flutter.

Swooping synchronously low over the trees, amid the heat of battle to wage,

Already some dead or dying, for more, this too, will be life's final stage.

Machine guns spit Aries counsel, lambasting each and all, to and fro,

Inflicting deep memory or mortal wounds on these whose country said, "Go!"

Perched safely in power seats, some men toy with governments, at play,

Feel not the scarlet anguish of the knights who fell in war today.

Not in protest or ruin of war, but in the depth of thy soul, find what is right,

Some will survive the conflict, but with Death, Life must forever fight.

|

|---|

|

|---|

|

|---|

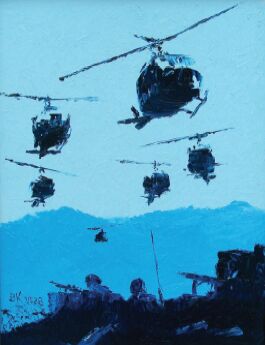

Comments from a Crewchief

In 1969, the 71st Assault Helicopter Company had a combat assault into a valley near LZ Center, which involved about fourteen or fifteen lift birds, and all but one (the last one in the flight) was shot down. The LZ was surrounded by hidden, reinforced North Vietnamese Army (NVA) bunkers. As the helicopters landed to drop off the American Infantrymen, a furious battle broke out, and only the last helicopter in the formation flew out. All the others were shot down where they landed, in only seconds.

A combat assault using about fifteen helicopters was normally the largest we were involved in, in the late 1960s. Most combat assaults used six, seven or eight lift helicopters, and were for the most part, almost routine troop movements. However, as I have had to explain to some of my veteran friends, The Assault was written with two very large combat assaults particularly on my mind; in fact, they were the two biggest assaults that I have ever been involved in.

The first large combat assault in which I was involved was on May 27th, 1968, when I was in the 176th Minutemen. I had been on CA's before, but this was special. Usually, an assault was flown by helicopters all from the same company, but on very large lifts, it was sometimes necessary to pull together helicopters from other units to have enough to do the job. On May 27th 1968, we were called to LZ Baldy for a combat assault. Leaving our assigned mission, we met many other helicopters, and lined up on the runway at LZ Baldy as instructed. We shut down the helicopters and milled about our birds, wondering what was up. My helicopter was second in line, so that put us in the first wave, a V of three. The pilots were called to a special briefing and returned some time later. When they returned, they told us that military intelligence had detected a very large force of North Vietnamese regulars moving into South Vietnam through some valley southwest of LZ Baldy. We were to put an American infantry battalion in there to ambush them.

The plan was to put as many infantrymen on the ground, as quickly as possible. The only good place to do this was a barren hilltop in the area which had once been an American firebase called LZ Little Joe. Little Joe had been abandoned for a long time, but it was perfect for what we had to do. The Vs of three, A Flight (3 helicopters), B Flight (another 3 helicopters), and so on all the way back to the last V of three, were to follow each other with about a seven-second separation.

I was in A Flight, my helicopter was in the A-2 position which is behind and to the left of A-1, which was the lead helicopter for the whole thing. A-3 was flying along the right side of my helicopter. About the time the pilots finished briefing us (each pilot briefed his own crew), the infantry arrived. About six of them came over to my helicopter and climbed in. The expressions on their faces seemed to say that they knew what was up. Everyone was quiet, serious, and any verbal exchanges were short, brief comments. We started the helicopters, and once all helicopters were ready, we took off, heading east, turning southwest as we climbed out and away from LZ Baldy.

Artillery had been dropping rounds into the area of the landing zone, but with the helicopters on the way, they stopped firing and helicopter gunships took over the LZ Prep. LZ Little Joe was so barren that not a blade of grass or tree grew on top of it. It was so clear that the gunships prepped the tree line below the LZ because if any enemy should be in the area, hoping to ambush us, it seemed likely that they would need the cover of the trees below the LZ. We went in hot also (door guns firing), unsure of the status of the enemy. On short final, it looked like this was going to be a piece of cake. No enemy fire from the tree line, and in a few seconds, these guys would be dropped off, and the next flight would be right behind us. With so many helicopters, we only had to make one trip into the LZ, so when we left the area we could return to our regularly scheduled mission.

It didn't turn out to be so easy. When we landed the helicopters on the LZ, a lot of loose dirt blew up. This was typical and no one was startled, but cardboard was, all at once, also flying up into the air and coming down through our rotor blades. The dirt was thick, and it was like being in a dust bowl, and there was intense AK-47 and machine gun fire all around us.

At first, it was impossible to see where the enemy was, but they were knocking a lot of holes in our aircraft. Both of my pilots were hit, but still able to fly. Some of the infantrymen on the cargo floor were also hit, and something like a sledge hammer knocked me down in my seat. It hit me with enough force to knock the wind out of me, and it was a struggle to get three deep breaths to start breathing again. I had been knocked down with so much force that my flight helmet was pulled forward covering my face. As fast as I could, I got up to get back into my seat, and looked around the cargo floor to see what had happened, while grabbing my M-60 again. Some infantry guy sitting behind the left pilot's seat was pointing to a spot on the ground below my gun mount, and yelling at me that, "He shot you!"

I looked over the top of my ammo can, and saw a Vietnamese guy looking at me as if he was seeing a ghost. His bullet had hit my armored chest protector, which we called our "chicken plate." In the headset built into the helmet, the pilots wanted to know if everyone was back on board. I gave them "Clear left," meaning we could leave, and then I noticed the spider holes all over the place. We had landed right on top of the North Vietnamese Army that our guys had wanted to ambush. I fired at the guy who had tried to kill me, and shot at some other spider holes as all of us in the A Flight got off of the top of that hill. It took less time for all this to happen than it takes to read what I have written so far.

|

|---|

My helicopter was shaking like a washing machine out-of-balance, and it seemed as though it would come apart in the air. I can't remember for sure, but I think all three of our helicopters were trailing smoke. Mine was, and we were also losing fuel. Bravo One (B-1), the lead helicopter in the second V of three, flew right over the top of the hill, following us. They didn't land, of course, but being the only thing the enemy gunners could see at that time, they got shot up just as badly as we had in the A Flight. The Huey in the B-2 position broke left, and B-3 broke right, none of them flying over the LZ. C Flight was far enough back that C-1 was able to take over formation lead, and took the rest of the helicopters out of the area.

We made it back as close to LZ Baldy as we could get before ditching all four helicopters in a flooded rice paddy (water up to our waists). From there, we carried the wounded to LZ Baldy. Once in the aid station there I saw many, many wounded, some looked worse than others, but I didn't hear of any of our guys being killed. The crewchief in the helicopter across from mine had caught a bullet between his head and his helmet. He was medically grounded for a few days to recover, and said it had given him a splitting headache.

Our helicopters were recovered from the rice paddy within a couple of days, and returned to our company base at Chu Lai; however, battle damage was so extensive that the Hueys were shipped back to the states for rebuild (or so they told us). I had to crew a float helicopter until the Army could issue me another one. Float helicopters were spares that no one wanted. In cases like ours (our company lost four in one day), a float helicopter would be delivered for use until another could be assigned, then the float was returned to the pool.

One thing is typical of all combat assaults, and that is the adrenalin rush. No matter how large or small the CA, your pulse always raced and the high level of readiness, looking for any sign of the enemy, being instant in your reflexes, was all a common denominator in the combat assault.

A second very large combat assault took place again, before the year was out, on November 20, 1968. I was transferred to Duc Pho, to fly with the 174th Assault Helicopter Company, near the end of my first tour in Nam. This was a DEROS Shuffle designed to keep one unit from losing all of its experienced people at one time, due to the fact that everyone served just a year, then went back to the States. (DEROS is the date your tour is over and you return home: "Date of Estimated Rotation Overseas")."The way the build-up went, a lot of units were scheduled to have all new replacements, except for the DEROS shuffles that nulled that out. Over a dozen of us from the 176th went to the 174th at this time.

I was assigned to the First Flight Platoon. Duc Pho had a reputation as a place too close to the enemy. It was a small LZ (in fact, it was a fire-support base), much smaller than Chu Lai, and probably no bigger than LZ Baldy. Within a few days, not far from Duc Pho, an F-4 Phantom had been flying low-level through a valley west of there, "Scud Running" (going under the clouds to avoid poor weather, not in reference to the Iraqi "Scuds" of twenty years later, which were missiles.) The F-4 was shot down, and the pilots ejected. The fighter was near the ground when he was shot down, so it was believed that the pilots would be somewhere near the wreckage. A crewchief in our platoon, from New Mexico, was the crewchief on the helicopter that was sent into that valley to look for the missing F-4 crew.

His aircraft commander was Warrant Officer John O'Sullivan. Mr. O'Sullivan, incidentally, was the most highly decorated Army helicopter pilot of the entire Vietnam War. He was a gutsy pilot, if I may use that expression. On the 18th of November, 1968, Mr. O'Sullivan and his crew entered the valley to search for the downed crewmen. They got caught in heavy enemy gunfire, and the crewchief was hit twice in the torso, both bullets missing his armor plate. The helicopter was also badly damaged and Mr. O'Sullivan managed to coax it to the far north end of the valley, putting it down on a hilltop out of range of the enemy gunners. Another helicopter from 174th was able to evacuate Mr. O'Sullivan and his crew, and what was a couple of real lucky shots for the North Vietnamese gunners were fatal for the crewchief. He died in the aid station at Duc Pho. I was assigned to be crewchief of the helicopter that Mr. O'Sullivan was assigned to as aircraft commander, and I flew as his crewchief for the next few weeks. Anyway, back to the Combat Assault.

The next day, November 19th, my helicopter was sent into the valley to look for the still missing F-4 crew. We had reports that the body of one was floating down the river that ran through the valley, and if possible, we were to recover him. We did a high-speed pass, low over the river, and all I saw for sure was the wing tip of the F-4 Phantom. I saw no other wreckage. There was also a shape we believed to be a body caught in brush on the river bank, near trees. With a quick look around the valley floor, we saw nothing else so got out of there. Another helicopter went in later, and I think they were able to recover a body, but the valley was too dangerous to be in, due to the heavy enemy presence. That night, we heard the explosions of many tons of bombs falling on that valley. When the Mission Board was posted for the next day, we were all on a CA. The platoon sergeant said we were all going into the valley where our friend had been killed. It had also been determined by someone that both pilots of the F-4 were dead.

That night, as I lay on my bunk, the light bulb, which hung from the ceiling by its own wires, was swinging in a small gentle arc, from the vibrations going through our quarters, due to the steady and continuous bombing of the valley. There was no single explosion, just a rumble of many explosions all night. Suddenly, at about 4AM or so, the bombing stopped. Soon, the orderly came in to get us all up, saying it was time to go. We called it Pitch-Pull time, meaning the time you were scheduled to take off. (The expression referred to working the flight control that increased pitch in the rotor-blades, making the helicopter lift off of the ground.)

It was still in the pre-dawn dark, when we took off from Duc Pho, and we were told to assemble on the runway at a Special Forces camp in the mountains, near the valley we were going to attack. Other helicopters from other units would join us there. We followed our instructions, and shut down on the Special Forces jungle runway, and waited for the infantry to arrive. This they did, in the large dual-rotor CH-47 Chinook helicopters. The CH-47's came in and landed, and the infantrymen poured out of them, and after their leaders organized them, they came to the helicopters to which they had been assigned. It was daylight at this point, and the CH-47's took off, leaving us to finish our mission. American artillery had been dropping rounds into the valley since the bombing had stopped a couple of hours earlier. When we cranked our helicopters to start the mission, the artillery was shut off, and attack aircraft took over the assault on the valley. We had A-4 Skyhawks dropping bombs, and our own helicopter gunships flying escort as well. Air traffic control was critical, since the high-performance jet fighters were dropping through the bottom of the clouds, and flying parallel to our flight path at much higher rates of speed. There were a couple of dozen water buffaloes, sometimes called VC or NVA "trucks" or "transports," on the south end of the valley where we entered. They were promptly killed by the aircraft gunners and we continued into the valley.

My helicopter was about half way back in the whole formation and the sight I saw up ahead was very impressive. From back in the formation, it was possible to observe a lot that you can't otherwise see. The A-4 Skyhawks came alongside of us, and when I looked back at where they were coming from, I could see the twinkling flashes of the Skyhawk twin cannons and thought how fearsome they looked. Looking to the front, I could see the Skyhawk's cannon shells exploding in fury as it plowed a quick path of destructive energy up the valley. As we reached the center of the valley, where the troops were to be dropped off, the attack aircraft had dropped all their wing mounted bombs, and with the helicopter gunships, they finished their final pass with just the cannon fire. Helicopter gunships used the mini-guns and rockets until we were all landed, dropping off our troops. With American infantry on the ground, all hostile fire stopped, and only the sound of our helicopters leaving the infantry behind could be heard. We were released to fly our regular missions, each to his own, and the large infantry force on the ground set about the business of cleaning out the valley. Some few enemy soldiers were captured in there. As I understand it, there was no enemy resistance. Most of the North Vietnamese Army force that had been there had managed to get out, going deeper into the mountains and jungle, toward Laos.

When I wrote the poem, The Assault, I could not ignore these two combat assaults that had left such a deep impression on me, from 1968. Describing them as I have done here, seems to fail in trying to share with anyone the tension in the air, and the mixture of fear and excitement, as well as the very sobering effect it all has on frail human life, when it is suddenly thrust into such a merciless environment. While smaller assaults were much more common, with the helicopters involved in them flying several lifts between the pickup zone (PZ) and landing zone (LZ), I could not write about combat assaults without acknowledging the two that made the greatest impression on me over my three tours in Nam. Other combat assaults, while fewer aircraft were involved, still involved danger and excitement. There were assaults with the enemy there ahead of you, and we had assaults in which the LZ was mined and booby trapped. You just never knew what would be there to meet you, but the one thing all combat assaults were about, was our effort to take the fight to the enemy's camp.

|

|---|

American Bases in Vietnam

If the American bases in Vietnam could be classified by their size, there were generally

about three types. The largest bases were the ones like Da Nang, Cam Ranh Bay, Chu Lai and a

host of others. These bases had runways long enough to support fighter aircraft, and many other

types of jet and piston-powered aircraft. These also had the hospitals and many other facilities,

and were distinctive in being used by multiple branches of the military, such as Air Force, Marine,

Navy and Army. Second in size to the base was the fire-support base. It would have a runway, but

only for smaller aircraft. Various units from a brigade or division might be stationed there, and the

fire-support base would support the smaller fire bases. Fire-bases were usually located on remote

hilltops or other tactical locations out in the field. They were battalion-size and were equipped

with helicopter landing pads, but no runways for fixed-wing aircraft.

Nighttime was usually quiet in Vietnam. Everyone (even if only sub-consciously) would be

listening for unusual noises. Nighttime in Vietnam seemed to imply a greater threat, and listening

for threats was more important than trying to see a threat.

Fire-support bases, such as Duc Pho (LZ Bronco) and LZ Baldy, were the same type of

base as the more famous Khe Sanh. The enemy would try to penetrate these at night, and sneak

around collecting intelligence and committing sabotage. Fire bases, on the other hand, being so

much smaller, were more often the target of the enemy ground attacks. On a few occasions, the

attacks on a fire base could be fierce, such as on LZ Professional, where the U.S. Army had to

call in strikes right on top of Professional to get the enemy off. Bases and fire-support bases, on

the other hand, usually received more indirect fire, such as from the enemy mortars, or 122 mm

rockets. LZ Bronco at Duc Pho was hit by indirect fire around the clock, day and night in 1969,

for example.

|

|---|

Air Vietnam

South Vietnam seemed the epitome of contrast. Provincial capitals across the country

were constructed of European French-style buildings, while stone-age villages and hamlets were

constructed in the most ancient of building techniques: from crude booby traps to state-of-the-art

ordinance of the time. The large airfields were also a mix of aircraft, from very old piston and

propeller types, to full jet and turbo-prop types. Fixed-wing and rotor-wing aircraft all moved

around and about each other, doing their part of whatever it was. South Vietnam also had its

own civilian airline, made up mostly of old piston and propeller aircraft like the Douglas DC-3 and

the Curtiss C-46. They also operated the French-built Caravelle passenger plane in their airline

fleet.

Flying on a civilian airplane, operated by the South Vietnamese airline, was a true Third

World experience. In January of 1968, Ben was sent from Nha Trang to Da Nang on a C-46 like the

one in this colored pencil drawing. He was very surprised to find that the Vietnamese passengers

were flying with live animals, mostly chickens, bundled in their laps. On this flight, at least one pig

escaped his owner near the front of the plane, and was chased by the hapless old rice farmer all

the way to the back of the plane, where (with no where else to go) the pig was easily re-captured.

Later, Ben learned that they traveled with live animals for the purpose of having food to eat on

their trip. The live animal needed no refrigeration (which was not available in much of the country,

anyway.)

|

|---|

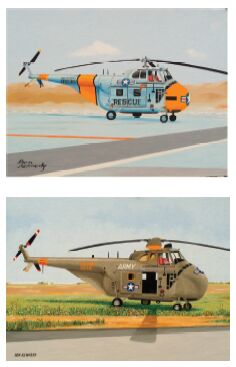

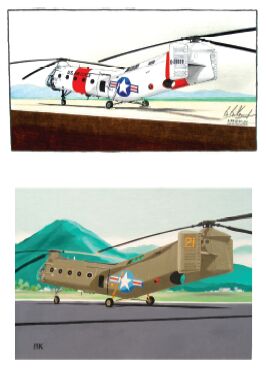

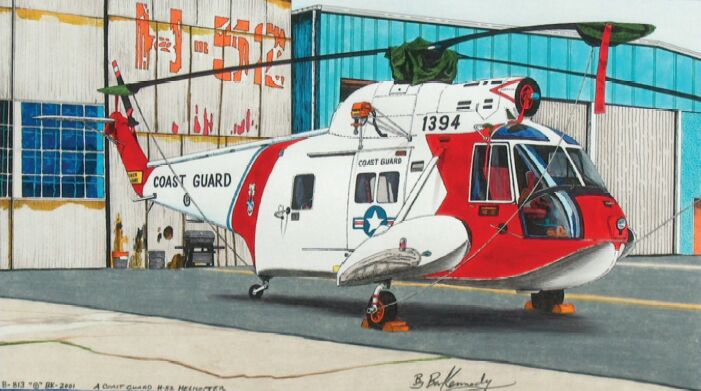

The H-19

The U.S. Air Force operated the H-19A and the H-19B models, in the rescue role. In January

of 1963, the U.S. Air Force sent an advisory detachment to Tan Son Nhut Air Base, in South Vietnam,

to train the Vietnamese Air Force (VNAF) pilots in the H-19 helicopter.

The U. S. Army operated the H-19C and H-19D Chickasaws. The H-19 helicopter was built by

Sikorsky, as the civilian model S-55. The U.S. Navy and U.S. Air Force also operated the H-19A and H-19B

models. The S-55 was also operated by the United Kingdom, Japan and France. (The French tried

to evacuate their casualties in Indochina with their Westland built S-55 [H-19] helicopters, based in

Laos. The overall effort was not successful as the Viet Minh prevailed over the French making air

operations almost impossible.) The H-19 was used in South Vietnam during the initial involvement

of the U. S. Military in the war. These helicopters were soon transferred to the South Vietnamese

and thus became the type used to develop the helicopter branch of the South Vietnamese Air Force.

VNAF would eventually receive the H-34 and later the UH-1 Huey helicopter from the United

States.

|

|---|

The H-21

This is a colored pencil drawing of the Piasecki Helicopter in the colors of the U.S. Air Force

H-21 Workhorse. This particular paint scheme was found on the H-21 in an Air Force museum in

California. The Piasecki Helicopter served in the U.S. Air Force and the U.S. Army as the H-21. Canada,

West Germany and the French also used this helicopter in their armed forces. It was first flown

in 1952, and the H-21C Shawnee went to South Vietnam with the U.S. Army in 1962. The

U.S. Air Force and other operators of the Piasecki Model 44 (H-21) flew the helicopter under the

name of Workhorse. The Piasecki H-21s saw combat in Algeria, serving with the French in the

1950s. Piasecki Helicopter Corporation became the Vertol Aircraft Corporation in the mid-1950s,

and Vertol in turn merged with Boeing, to become The Boeing Vertol Company, which went on to

produce the CH-47 Chinook Helicopter.

|

|---|

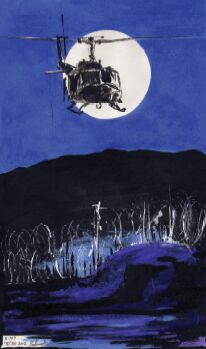

NIGHT FLYING

Night flying in Vietnam was very different from what one might experience in the West,

because there were no street lights or other such lights across most of the landscape at night.

With a full moon in summer, it could seem to be almost daylight down below. In the Monsoon

Season, however, low clouds and frequent rain caused poor visibility, making night flying very

dangerous. These dangers often extended into the daylight flying hours. Flight operations were

very hazardous, since visibility could be as little as one-quarter mile. Sometimes aircraft were

grounded because the fog was so thick that you could not see as far as three or four times the

length of the helicopter.

During the monsoon season, aircraft would fly along routes like Highway One, because

navigation any other way was more difficult. To avoid mid-air collisions in the reduced visibility, it

was customary to fly with your landing light on. In the case of an A-4 Skyhawk or F-4 Phantom, you

could see their light coming toward you before it was possible to see the aircraft. It always gave

me goose-bumps to flash past them at times like that. Our airspeed would usually be eighty knots,

and the fixed-wing types could be flying at 150 to 200 knots. This made for a very high closing speed

and you had only a few seconds from the time you saw their landing light, until they were past you,

going in the opposite direction.

When navigating like this, along Highway One, southbound traffic flew along the west side of

the highway, and northbound traffic would keep to the east side of the highway. At night, GCA

(Ground Controlled Approach) was available to get us from Point A to Point B, but due to the

fact you were in the clouds, which could go all the way to the ground, these missions were very

hazardous because when you dropped below a ridge line or mountain range, you also dropped off of

the GCA radar, and the radar operator could no longer direct your flight to keep you from flying

into a mountain.

|

|---|

|

|---|

The Huey Helicopter

The Huey Helicopter could be outfitted with several configurations of weapons systems. The

various configurations were usually made up with some combination of machine guns, rocket pods

and a grenade launcher. No matter how the helicopter was configured, the crew would usually be

flying at maximum weight, since the crewchief and gunner would take as much extra ammunition

for the door guns, and grenades of various kinds, as their helicopter could lift.

Watching one of these helicopters take off was an event in itself, and could induce a couple

of bystanders to bet on how much runway it would take for them to go through transitional lift.

Transitional lift was the point at which the helicopter would transition from being in ground effect,

to being out of ground effect. When close to the ground, the air mass forced down by the rotor

blades (to lift the helicopter) would hit the ground, and build up pressure between the helicopter

and the ground. This was the condition of being in ground effect. One measure of a helicopters

power is its ability to hover out of ground effect, such as hovering very high up in the air.

|

|---|

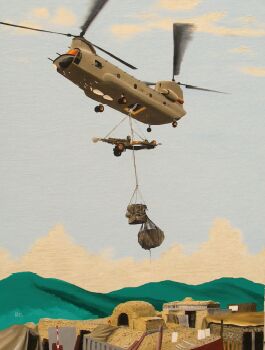

CH-47 CHINOOK

First flown in 1961, the Ch-47 Chinook is a product of the Boeing Vertol Company. The U.S.

Army used the CH-47 in the assault support helicopter company role in Vietnam. The Chinook

Helicopter is still serving in the military and will likely be around for some time to come. In this

oil painting the Chinook is portrayed in a familiar scene for many veterans of the Vietnam war.

The Chinook is delivering a 105 Howitzer to a fire-base located on one of the many mountain tops

in South Vietnam.

|

|---|

CH-46 SEA KNIGHT

The U.S. Marine Corp. and the U.S. Navy favored the Boeing Vertol Model 107, in military

service as the CH-46 Sea Knight. The U.S. Marines used the Ch-46 extensively in South Vietnam.

|

|---|

The Sikorsky S-58 Sea Horse / H-34 Chocktaw

The Sikorsky S-58 was a very successful helicopter in both military and civilian service. The

U.S. Marine Corps operated it as the Sea Horse, the U.S. Navy designated theirs as the Sea Bat, and

the U. S. Army called its H-34 helicopters the Choctaw.

|

|---|

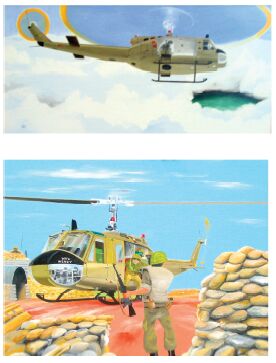

VFR on Top (Top painting above)

This oil painting has been nicknamed "Looking for a Hole" by members of my family. It

portrays a UH-1 helicopter looking for a hole in the clouds through which they might descend. In

Vietnam, during the monsoon season, helicopter crews would sometimes climb out above the

weather and fly toward their destination in the more desirable conditions on top of the cloud

cover. To avoid flying into a mountain side, however, it was necessary to descend through a hole in

the clouds, so you could see the Terra Firma below.

War Weary (Lower painting above)

In this painting, a Huey helicopter has landed on an American fire base in Vietnam. Fire

bases supported the infantry units in the field using the Huey to shuttle supplies and personnel back

and forth from the fire base to the field.

Vietnam is a country of many different terrain features, from the flat river delta region

south of Saigon to the rolling piedmont hills north of that city, on farther north to the mountains

and terraced rice paddies of the Central Highlands.

This oil painting shows the extensive use of sandbags on the typical red clay hill top of so

many American fire bases in that part of South Vietnam called I-Corps.

|

|---|

OH-58 Kiowa

on the Maintenance Ramp

The Bell Helicopter Company developed the Jet Ranger and the U.S. Army operated it as

the OH-58 Kiowa. In this pencil drawing a Kiowa sits in the maintenance area of a unit in South

Vietnam. In the first part of American involvement in the war, maintenance tents, such as the one

this OH-58 sits next to, were common shelters for maintenance. These tents were used as hangers

until the engineers could build the wood frame structures that were so common in the second half

of the war.

The OH-58 Kiowa is still in the military service, having gone through the necessary

modernization and upgrading to make it suitable for the contemporary battlefield.

|

|---|

CH-47 MAINTENANCE RAMP

A large wood frame shelter provides hanger space for the unit operating this Boeing Vertol

CH-47 Chinook. This helicopter sits in the maintenance area of its unit, and has numerous panels

removed, or opened up for work on the aircraft. The engines and rotor blades have also been

removed. Helicopter maintenance crews spent long hours keeping the helicopters in good flying

condition so that they would be mission-ready when called upon.

|

|---|

AH-1G COBRA

This Bell Helicopter AH-1G Cobra is in its maintenance hanger, undergoing repair. The

P.A.&E. initials on the left side of the drawing represents the civilian contractor and construction

company that did much of the construction work for the military in Vietnam. The company was

Pacific Architects and Engineers. The TAMMS sticker is in reference to The Army Maintenance

Management Systems, simply referred to as TAMMS. It was the Army paperwork system, used to

keep track of the maintenance and unit readiness of any army unit, anywhere in the world.

|

|---|

H-43 Huskie

Kaman Helicopter produced the H-43 Huskie. This helicopter was used by the U.S. Air

Force in crash rescue and fire-fighting duty. Pedro was the call sign used by Air Force H-43

Helicopters in Vietnam. In this oil painting, Pedro waits on a barren hill top with low cloud

cover moving over the jungle-covered hills nearby. The pilot can be seen in the background, near

the edge of the hilltop, studying the changing weather.

|

|---|

Kaman Huskie and Douglas Globemaster

This Kaman H-43 Huskie is on display at an Air Force Museum in California. The Douglas C-124

Globemaster II in the background is another Vietnam era aircraft, and was used to fly cargo

into South Vietnam during the 1960s. In those days, the Air Force operated both MAC and MATS.

MAC was the Military Airlift Command, and MATS was the Military Air Transport Command. In the

mid-1970s MATS was dissolved and its mission absorbed by the Military Airlift Command. By that

time, the C-124 had been retired from service, making the war in Southeast Asia the last war the

plane flew in support of.

|

|---|

Bell 47 / OH-13 Sioux

The Bell Model 47 was operated by the U.S. Army as the OH-13 Sioux. It was used by the Army

in the liaison role in Vietnam. It was also used by the Army flight school to train Army aviators,

until being replaced by the TH-55.

|

|---|

OH-6A

This pencil drawing depicts a Hughes OH-6 helicopter flying close to the ground trying to flush

out the enemy. The term LOH (light observation helicopter) was usually identified with the OH-6

Cayuse, operated by the U.S. Army in Vietnam. LOH was pronounced "loach" and though there

were other light observation helicopters, the loach was a nickname for the Hughes OH-6 Cayuse. As

if to anticipate the hazardous missions this helicopter would undertake, it was designed with crash

survivability in mind. The egg-shaped design allowed the rotors and transmission to shear off in a

crash, keeping them from coming down on top of the crew. Maybe these features were why it was

assigned the hazardous duty which it undertook.

|

|---|

OH-23 Raven

The Hiller Aircraft Company produced the OH-23 Raven, which was used extensively in Vietnam,

in the same role as the Bell 47 Helicopter. The Hiller civilian version proved to be useful in

the post-war business of crop-dusting.

|

|---|

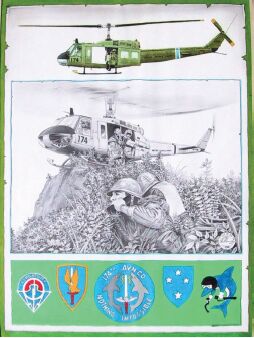

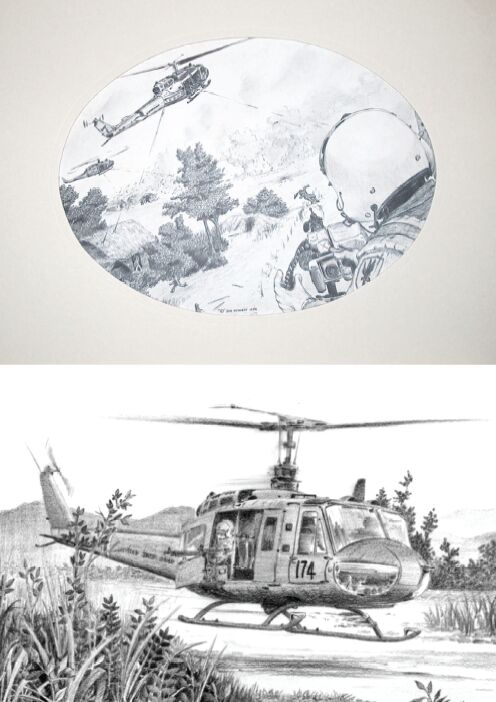

Dolphin 223

Dolphin 223 is a UH-1H Helicopter, based out of Duc Pho, South Vietnam in 1969. The

helicopter was assigned to Engineer (crewchief) Thomas Gauby. The pencil drawing was done for

him and is in his private collection. The helicopter was operated by the 174th Assault Helicopter

Company, and this drawing shows 223 in a field location somewhere in Quang Ngai Province.

Helicopter landings like this were common place, and occurred many times a day by helicopters

all over South Vietnam. In this picture, you can see the infantry providing perimeter security in

front of the helicopter. They would be in a full circle of security around the helicopter, since these

craft were such a desirable target for the enemy. At the helicopter, an infantryman is talking to

the pilot, probably giving him a late message, or updated information. Another infantryman is

talking to Tom, the crewchief. He would most likely be asking Tom to take some letters back to

base camp, to mail for the guys out here in the field. Two more infantrymen are at the cargo door,

sending equipment back for repair or issuing new equipment to the troops at this location. From

landing to take off, all this activity would only take about 30 seconds and rarely ever lasted for a

full minute. This helicopter would make many such landings at various locations throughout the

day.

|

|---|

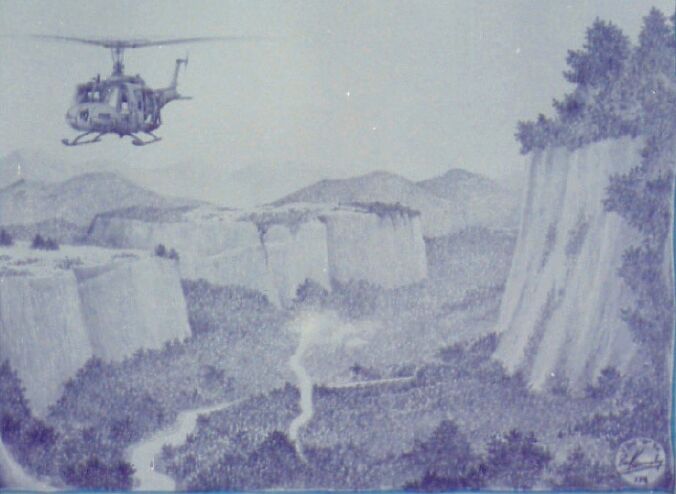

Pinnacle LZ

Mountain flying is always hazardous, and it was no less so in Vietnam. Helicopters were

required to land and take off from mountain pinnacles to support combat troops operating in the

steep mountainous terrain. In this picture, a helicopter from the 174th Assault Helicopter Company

is lightly touching down on a pinnacle. The helicopter would still be operating under power, as

though it were in flight, so these conditions were not such as where the crew could come to a full

landing, and reduce power while people and equipment were transferred. This picture is in the

collection of Tom Gauby, a veteran of the 174th Assault Helicopter Company in Vietnam.

|

|---|

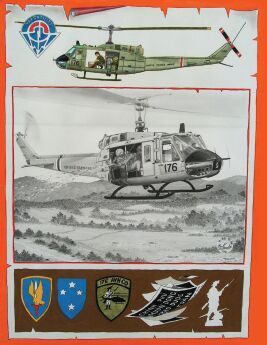

Leaflet Drop

This picture shows a Huey helicopter from the 176th Minutemen on a Leaflet Drop Mission.

The helicopter was flown over a pre-selected route while a military intelligence officer would throw

leaflets out the right side. He would board the helicopter with a few boxes of leaflets, and they

would all be scattered over the landscape along the designated route. .

|

|---|

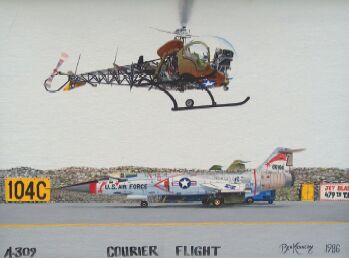

Courier Flight

This oil painting depicts the Bell OH-13 Helicopter, early in the Vietnam War, taking off

from an American Air Base. The F-104 Starfighter in the background was used early in the war in

the ground attack role. The mix of technologies during that war is brought into sharp focus by the

realization that the F-111 would be flying attack missions in Vietnam before the United States put

a man on the moon in 1969.

|

|---|

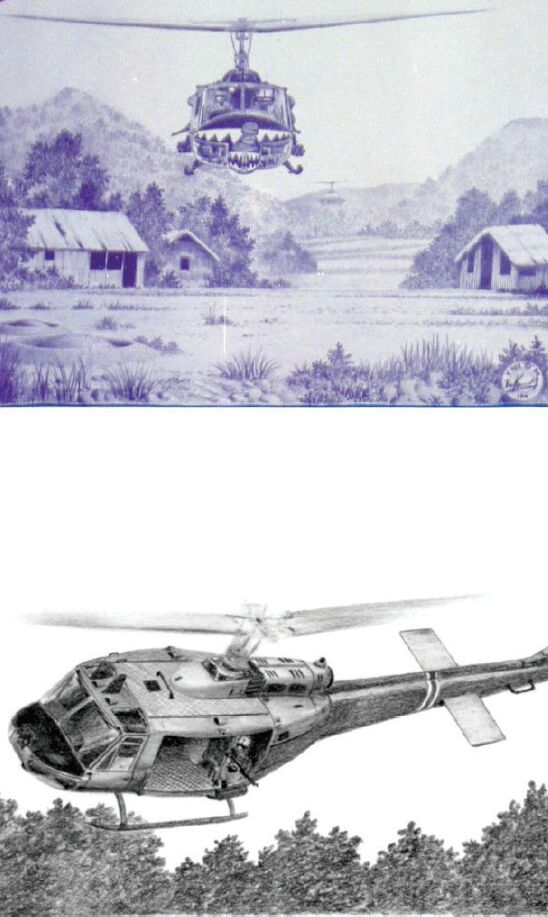

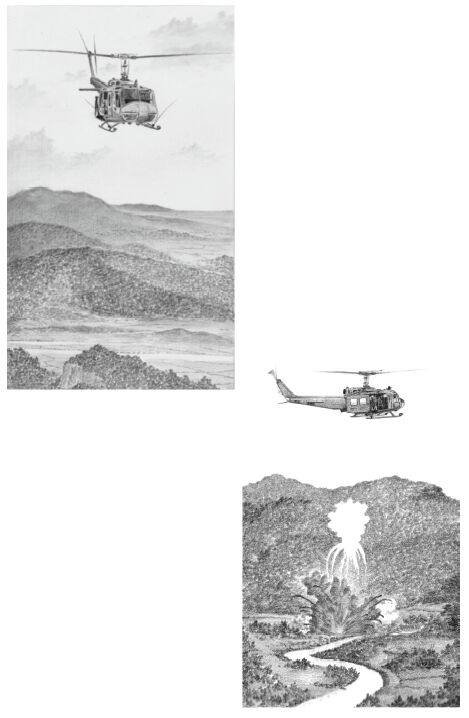

Low Level Armed Recon (top)

Here you can see two gunships on a low level armed reconnaissance. The helicopters are

flying over the countryside, looking for enemy activity. The UH-1C Huey Gunships are from the

174th Assault Helicopter Company at Duc Pho, and are assigned to the 3rd Flight Platoon, called

the Sharks. (Notice the sharks teeth on the front.) While it was always possible to catch some

enemy courier alone, carrying a satchel of papers or some group of enemy soldiers, such as a squad

on the move, it was more often that you could find some enemy firing position, such as a site for

launching rockets or mortars, or a site that had been dug for a .50 caliber anti-aircraft gun. Looking

for signs of this kind of activity was very much a part of the low level recon mission. For this

reason, recon missions like this were usually flown at lower air speeds, which made you an easier

target for enemy gunners, if you found them. If you found enemy positions that appeared to be

unoccupied, they were plotted on the map, and the location given to headquarters for analysis of

enemy activity in that area.

Search and Rescue (bottom)

This pencil drawing shows a Huey in low level flight, making a generally wide left turn. This

was the most common bank angle in low level turns, but if in contact with the enemy, the bank

angle could be much steeper. The cargo floor is empty, allowing for much greater maneuverability

at low level. In this drawing, the crew is involved in a search and rescue operation. Such missions

were flown when another aircraft was shot down in your area of operations, and the status of the

lost crew members was as yet unknown.

An example of a mission like this would be when the crew of an F-4 Phantom ejected in the

Central Highlands. A search for either survivors or the bodies of the crew would be conducted. If

the bodies were located, plans to recover them would be made. During these missions, you also

searched for evidence of the enemy's position, since the enemy had to be in the area to shoot

someone down.

|

|---|

Low Level, en route

This pencil drawing represents a UH-1 Huey flying low level on a combat assault mission. At

this point, they are flying over an Army tracked cavalry unit on the move. In the distance, other helicopters

can be seen leading the way. This drawing is in the private collection of Paul Latham. This view of

a combat assault en route was a development and outgrowth of a very old picture that had been

drawn in those days of a combat assault landing at the LZ.

|

|---|

Psy-Ops

The 14th Combat Aviation Battalion flew many different missions in Vietnam. The great

versatility of the helicopter gave many options to the Army, Navy, Marines and Air Force, as they

employed their helicopters in the war. This drawing, a detail from a larger piece, is of a UH-1H

helicopter from the 174th Dolphins, based at Duc Pho, South Vietnam, in 1969. Here, they are on a

Psy-Ops mission. An Army Intelligence Officer has a tape recording he plays over a loud speaker, as

the helicopter flies over the jungle. This mission was flown in the early morning hours, and the crew

came upon campfire smoke as it drifted out and above the trees below. The military intelligence

officer switched off the tape and started talking to the North Vietnamese camped below. Some

irritated North Vietnamese soldier fired a short burst of AK-47 fire up through the trees, but the

Psy-Ops officer told us to hold our fire. He continued talking over the loud speaker as we flew on,

continuing our mission. This piece is in the collection of Mel Lutgring, a veteran of the 174th Assault

Helicopter Company during the Vietnam War.

|

|---|

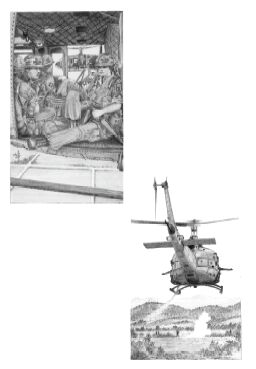

Combat Assault, en route (above, upper left)

Simply, this drawing shows some infantrymen on the cargo floor of a Huey, on a combat assault

mission. Out the right side door, another Huey is flying alongside them. In this formation arrangement,

the helicopters would be in Vs of three: one helicopter out in front, with two more behind him,

one behind and to his left, the other behind and to his right. This would put the two following the

leader directly across from each other. Another V of three could follow the first V of three, and

the entire formation could be made up of several Vs of three. When this type of formation was

used, it was normally because the Pick-up Zone (PZ) and the Landing Zone (LZ) were large enough

to accommodate three or more helicopters at one time. If the PZ and LZ were large enough, the

V formation offered the advantage of moving the most people from one place to another, in the

smallest amount of time. It also put the largest number of troops into the LZ on the first wave, and

allowed for the largest number of rear guard troops to remain in the PZ for the last Lift out.

Short Final to the Boonie LZ (above, lower Right)

In this drawing, a Huey is approaching an infantry unit in the field. The helicopter is only a few

seconds from landing, and the approach is being made to the smoke from a smoke grenade which the

infantry unit threw out for the helicopter. The purpose of the smoke grenade was to serve in helping

the helicopter crew locate the exact position where the ground unit wanted them to land. It came in

various colors, such as white, purple, red and yellow. The air crew, upon spotting the smoke, would

acknowledge to the unit on the ground that they saw their smoke, and would then name the color.

The ground unit would confirm the color of smoke that they had thrown, and the air crew could

then shoot their approach to landing, noting wind conditions on the ground by the characteristics

of the smoke in the air. Sometimes the enemy tried to lure a helicopter in to them, so they could

destroy it, by popping smoke if they saw one that seemed to be searching for smoke. This is why

it was vital to have the air crew identify the color, and the ground unit to verify that color before the

helicopter came in to land.

In this drawing, you can see excess fuel being vented overboard on the left side of the helicopter,

below the engine. The fuel pump delivered the amount of fuel to the engine, which the fuel control

required for the power setting being used at that time. When landing, power was reduced, causing

a short period of time when the fuel control would have excess fuel about to enter the combustion

chamber of the engine. To make the engine more responsive to the pilots demand for power, the

fuel control dumped excess fuel overboard when power was reduced. Since 1973, or there about, this

excess fuel (from all jet engines) has been contained, and vented back to the fuel tanks.

|

|---|

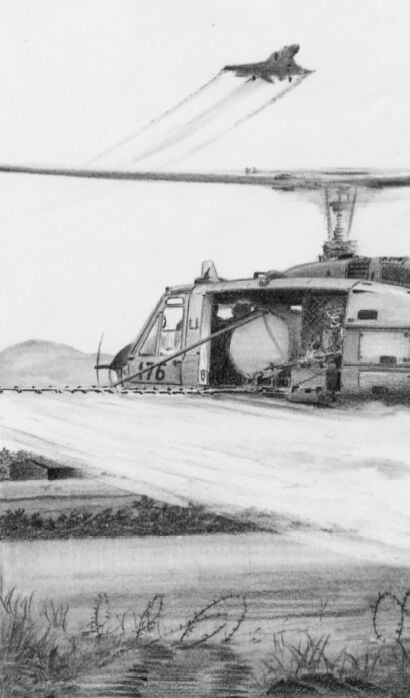

Chemical Spray Mission

This Huey is on a Chemical Spray Mission. The area is south of Chu Lai, and the

F-4 Phantom

at the top of the picture would be on approach to landing at Chu Lai. There were two chemical

missions that the helicopters might typically fly, and both missions were done only on occasion, as

needed. One was insecticide, to control mosquitoes near the American Base Camps. The other was

the well known (infamous) Agent Orange, or defoliant. This was dispensed by helicopter, around

the perimeter of American fire bases to clear away foliage which the enemy could use as cover, if

attempting to sneak up on the base.

|

|---|

The Kill (above, upper drawing)

This pen and ink drawing is the oldest drawing the artist has in his private collection. It was

done not long after returning from Southeast Asia, and shows helicopters on short final, a few

seconds from landing, on a combat assault. The enemy was caught unprepared and chaos on the

ground will soon intensify as the helicopters drop the first load of American infantry. At this point,

no friendlies are on the ground, but the second wave of helicopters coming in, as well as all

those that follow after them, will have to keep track of the American units on the ground as well.

The helicopter door gunners must be very careful after the first troops have been inserted into the

landing zone. It is also important to get as many more friendly troops in their LZ as quickly as

possible, to increase their numbers for what will become a running gun battle with the enemy while

he tries to get organized.

Low Level On The Deck (above, lower drawing)

In 1968 and 1969, Hueys did a lot of low level flying in the I-Corps area. Flying at about

eighty to one-hundred knots, sometimes only two feet above the ground, these low level flights

were always made at below tree-top level. The purpose was to avoid anti-aircraft fire, which

was typically from AK-47s but could be from .51 caliber anti-aircraft guns that showed up in the area

on occasion. These heavy machine guns were lethal to helicopters. Some foliage can be seen on the

cross tubes of the helicopters skids. At these low altitudes, it was not unusual to drag the skids

through the tops of weeds, bushes and trees, collecting plant material souvenirs, or testaments as

to how low you had been. If a sudden wind gust or air pocket hit the helicopter at just the right

time, it could cause a crash. (Many helicopters were lost due to various such accidents.) Most of

the time, though, these low level flights were uneventful. Only rarely did striking foliage ever cause

any damage.

|

|---|

Flying a Radio Relay Mission (above, upper drawing)

Radio relay missions were flown by helicopter crews on occasion, when it was necessary to

relay radio signals from some unit on the ground to the headquarters for that unit. Atmospherics

could sometimes interfere with the FM radio signal, especially if the unit was in a deep jungle

valley, with mountains all around. This was especially troublesome during the monsoon season,

when low cloud cover also impacted radio traffic. Radio relay missions were flown at whatever

altitude was necessary, and this would usually be as high as practical. Five thousand feet was not

unusual, but as much as ten thousand feet above ground level (AGL) might be used. When flying

a MACV mission to an island off the coast of South Vietnam, 14,000 feet above sea level was

frequently used by Army pilots, based on the theory that an engine failure half way between the

island and the coast of South Vietnam would require at least 14,000 feet to autorotate to dry

ground.

Directing Artillery Fire (above, lower drawing)

This helicopter is spotting artillery. A white cloud burst marks the area where artillery will

be impacting, and some artillery shells can already be seen hitting the target. When spotting for

artillery, the Huey would stay well away from the impact area, and out of the line of fire. It was not

unusual to see white cloud bursts over the Central Highlands in 1969, and they always reminded us

to check with Red Leg to determine if any artillery fire missions would be coming through where

we were flying.

|

|---|

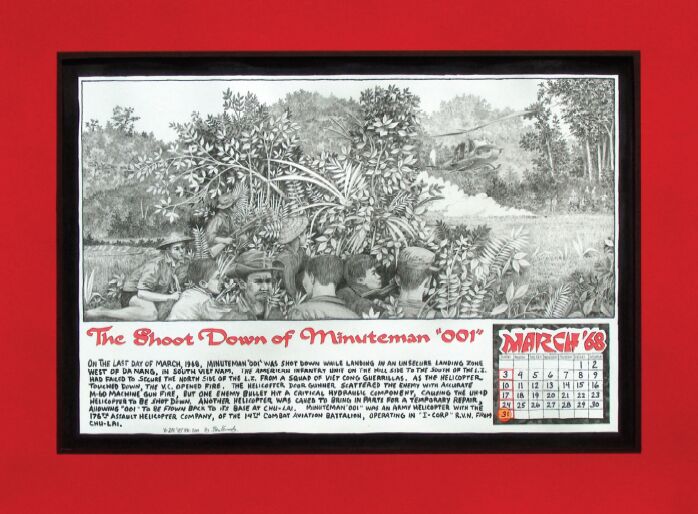

The Shoot Down of Minuteman 001

This pencil drawing is a scene of the terraced rice paddies and the surrounding tree covered

hills near Da Nang, where Minuteman 001 was shot down, by a single bullet, out of a fusillade of

bullets fired from a platoon of Viet Cong with SKS (Russian/Chinese) Rifles. This helicopter is the

same helicopter involved in the Near Mid-Air Collision with the Air Force A-37 South of Chu Lai,

as depicted in the next drawing below. The only bullet to hit the helicopter did

so at a point where it cut a hydraulic line. The crew was able to land the helicopter. The enemy

fled when the helicopter door-gunner returned fire. The maintenance recovery

helicopter from Chu Lai was called to the location, and brought a new hydraulic line and hydraulic

fluid, so that temporary repairs could be made. The helicopter was then flown back to Chu Lai,

where it was based, and permanent repairs were made to the airframe where the bullet had

punched some holes.

|

|---|

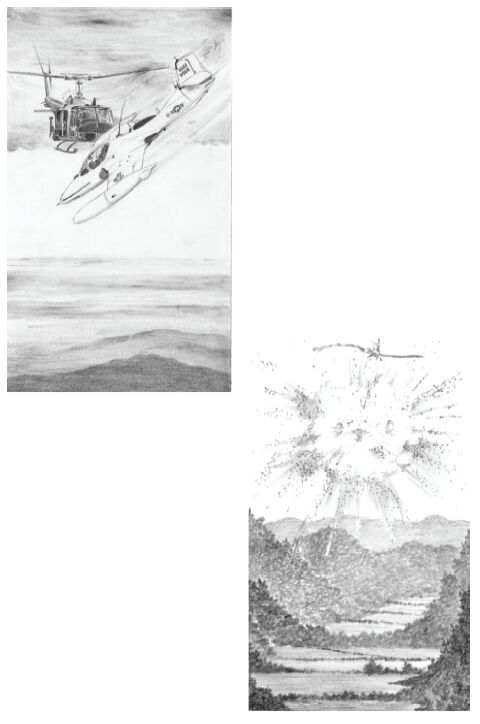

Minuteman 001 Nearly Collides with an A-37,

South of Chu Lai, RVN, 1968

(above, upper drawing)

South of Chu Lai, with monsoon cloud cover overhead, this Huey from the 176th Assault

Helicopter Company was heading west toward the mountains. The helicopter was flying just below

the bottom of the clouds, and narrowly missed being involved in a mid-air collision with an Air Force

A-37 as it dropped through the bottom of the clouds, apparently on course for a landing at Chu

Lai. The startled crews had no time to react as the aircraft crossed flight paths, with only a few

feet between them.

Helicopter Explodes, May 5, 1968 (above, lower drawing)

Near LZ Center, southwest of Da Nang, a Huey exploded in mid-air, seconds after take off

from that LZ. The Huey was from the 176th Assault Helicopter Company, based at Chu Lai, and six

infantrymen perished with the four-man helicopter crew. The aircraft commander for the Huey was

the 2nd Flight Platoon Leader in the 176th. The rotor blades were the largest part of the helicopter

to be seen on the ground afterward. It was believed at the time that they may have been hit with

an enemy rocket or RPG, but subsequent views are that maybe some enemy tracer fire hit the

fuel cells, causing them to explode.

(Note: The digital drawings for the two below items were damaged and have been removed.)

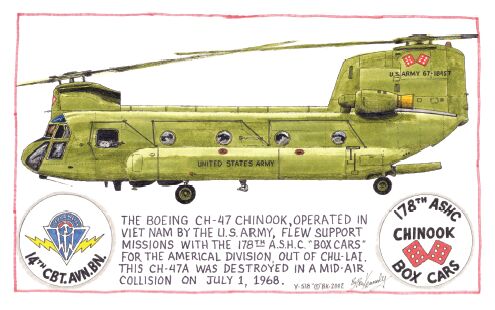

Mid-Air Collision on July 1, 1968

In 1968, the 14th Combat Aviation Battalion had some mid-air collisions. This drawing was

done while thinking about the loss of a CH-47 and its crew. A UH-1C Huey Gunship from the 176th

Assault Helicopter Company and a CH-47 Chinook from the 178th Assault Support Helicopter Company

were both on approach to the runway at LZ Baldy, a large fire support base, southwest of Da Nang.

The CH-47s forward rotor descended through the tail rotor of the Huey. With its forward rotor

shattered, the Chinook went nose first into the ground. The mid-air collision was too high for that

crew to survive. The UH-1C was very fortunate in that they were able to do a procedure called an

anti-torque auto-rotation to the ground, and they were thus able to survive.

Mid-Air Collision on June 13, 1968

This drawing was made remembering a mid-air collision between an Air Force O-2 Skymaster,

and a Huey helicopter from the 174th Assault Helicopter Company. In 1968, an Air Force O-2 fixed wing

aircraft flying above the Huey from the 174th, near Duc Pho, flew into the rotor-head of the

Huey. Both aircraft fell to the ground with no survivors.

|

|---|

Chinook, 14th CAB, Boxcars

This colored ink drawing represents a Chinook Helicopter in the 178th Assault Support Helicopter Company (ASHC) which was

destroyed near LZ Baldy in 1968, as the result of a mid-air collision with a UH-1C Huey gunship

from the 176th A.H.C. Both helicopters were from the 14th Combat Aviation Battalion, based at Chu

Lai.

|

|---|

UH-1H #66-16511

This UH-1H Bell Helicopter (Army Serial Number 66-16511) was operated by the 174th Assault

Helicopter Company, of the 14th Combat Aviation Battalion, stationed at Duc Pho, South Vietnam.

The helicopter was destroyed in a crash on April 23rd, 1969, after some contaminated fuel was taken

aboard at a Special Forces camp in the Central Highlands. After refueling, 511 flew to a U.S. infantry

base at LZ Liz to pick up a passenger for Duc Pho. It was late in the day (but still daylight), and

the crew had been expecting to return to their company area, finished with the days work. With

the passenger on board, and still climbing on their departure from LZ Liz, the high side governor

failed from the contaminated fuel, which allowed the engine to spool up to disintegration. The

engine exploded and 511 went down hard. The helicopter was broken into three pieces when it

hit the ground. The cockpit was crushed, the skids were flattened and all five fuel cells ruptured.

The transmission tore out of its mounts and the rotor head snapped off. The tail-boom broke off in

the area of the blue and white stripes that indicated the helicopter was assigned to the 174th. All

persons on board survived the crash.

|

|---|

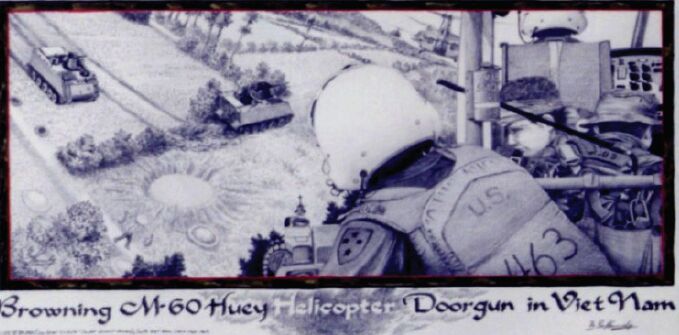

UH-1C Hog

This mixed media drawing shows a side profile view of a UH-1C Huey Hog. The Hog was

a term given to the UH-1C armed with all rockets. In this case, the helicopter was armed with 48

rockets, which can be seen below the helicopter, but not to scale with the Huey. A large round

cylinder assembly for rockets, containing nineteen rocket tubes, was an alternate system for the

Hog, but with nineteen rockets on each side, (instead of twenty-four,) the alternate system

would only provide a total of thirty-eight rockets in that configuration.

|

|---|

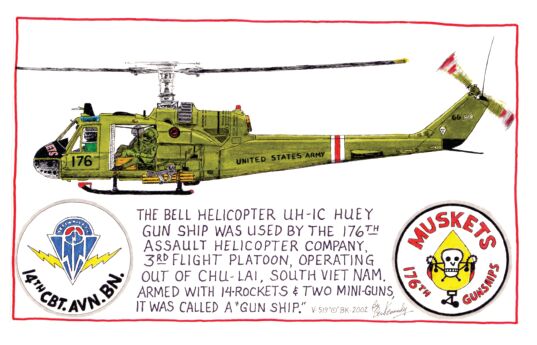

UH-1C

The Huey Gunship had been a UH-1B model in the early days, and would have been armed

with twin M-60 machine guns on each side, which were fired by the pilot, as well as the M-60 fired

by the right door-gunner, and the M-60 fired by the crewchief from the left door-gun position. The

helicopter would also be armed with fourteen rockets, seven on each side. Later, the UH-1C was

developed, using dual-hydraulic systems, and accumulators to make it better able to withstand

battle damage. The UH-1C gunship was configured as the UH-1B had been, except the M-60 weapon

system was replaced by the more aggressive mini-gun, which fired the same 7.62 mm ammunition,

but at a much higher rate (up to 6000 rounds per minute) of fire.

|

|---|

UH-1D

This is a profile drawing of a very old UH-1D Huey, in the colors of the 176th Minutemen. The

early Hueys suffered inadequate air filtration going to the engine. The result was a loss of power

as air filled with dust and sand went through the engines. To compensate for the loss of power, the

crews would try to reduce weight on the helicopter by removing all the insulation blankets, and as

many seats as possible from inside the helicopter. They also removed cargo doors, and on occasion

even the pilots doors, in an effort to get rid of a few pounds of weight, hoping to be able to replace

that weight with a few more pounds of cargo. The hard wear-and-tear on the engines, caused by

the lack of filtered air going through the engine, was a severe penalty especially on a combat

assault, when you could only carry four (maybe five) combat equipped American infantrymen. For

example, if three UH-1Ds each took four infantrymen into the LZ on the first lift, you would have

only twelve men there to secure and hold the LZ until reinforcements arrived on the next lift.

The later UH-1H helicopters, with stronger engines and better air filtration for the engines could

carry six fully equipped infantrymen into the LZ, putting eighteen men on the ground to do the

job previously done by a lesser number.

|

|---|

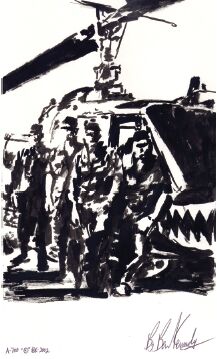

The Pilot

This Impasto palette knife painting in oil, shows a helicopter crew man in Vietnam with

his Huey. The Huey was usually flown all day, making it necessary to work on the aircraft after night

fall, getting it ready for the next day. Many crewchiefs worked well into the night taking care of

their helicopter, and then they flew a full schedule the next day. War is twenty-four hours/day, for

seven days-a-week. You rested when you could, but always lived close to your helicopter.

|

|---|

Night Attack

This palette knife oil painting depicts a Huey gunship attacking an enemy target with rockets.

The low light level, typical of sunrise or sunset, is probably at sunset, where some enemy activity

has been detected. The enemy would come out of hiding in the evening and attempt to conduct

their operations, movements and attacks as late into the night as possible. Such encounters with

the enemy at the dawn of the day were more unusual.

|

|---|

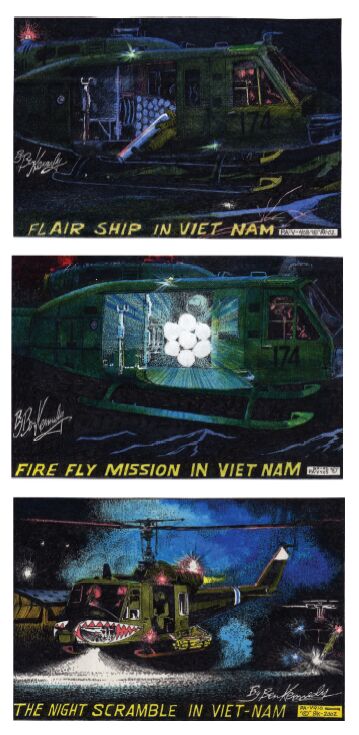

Various Night Missions

Flair ship missions were flown as needed. The helicopter was loaded with flairs for night

illumination, and if any unit was engaged in night combat with the enemy, they could call for the

flair ship to come out and drop powerful flairs over the battlefield. Huey gunships would escort

the flair ship, so that the unit on the ground could have assistance from the armed helicopter in

their firefight. These missions were flown for units in the field, as well as for fire bases that came

under attack at night.

Fire-fly missions were flown frequently in South Vietnam, and there were essentially two

kinds of illumination missions. In this colored ink work, the Huey helicopter is equipped with

multiple powerful spotlights (often aircraft landing lights) rigged together. The helicopter would be

outfitted with the spotlights that evening, for a

scheduled flight later that night. The flight may be planned for around midnight or so, and at that

time, they would take off to fly a pre-determined course, along roads, trails and rivers. At various

points, the light is turned on to see if you can surprise any enemy troops moving at night. Sometimes

the enemy was caught in the light, and Huey gunships following at some distance behind and below

the Huey with the light, would destroy the enemy while they were held in the light's beam. The

Huey with the light was usually called Fire-fly or Lightening Bug, depending on the unit, or

individuals preference for one name or the other. These missions were always planned ahead of

time, to fly a specific route, based on military intelligence estimates of enemy troop movement.

The night-scramble could be one of various missions, in support of a flair ship, or fire-fly, or

other action. You can see another helicopter preparing to take off behind him. These drawings

were prepared as a part of a series of postcards done by the artist.

|

|---|

The Sikorsky S-62 / HH-52

The Sikorsky S-62 was used by the U.S. Coast Guard as the HH-52. This helicopter used the

transmission and rotor components of the older Sikorsky S-55 (see the H-19 Chickasaw oil paintings

near the front of this book). Known as the Sea Guard, it flew support missions for NASA during

the early manned space program of the 1960s. This particular helicopter can be seen at the Mid-

Atlantic Air Museum in Reading, Pennsylvania.

|

|---|

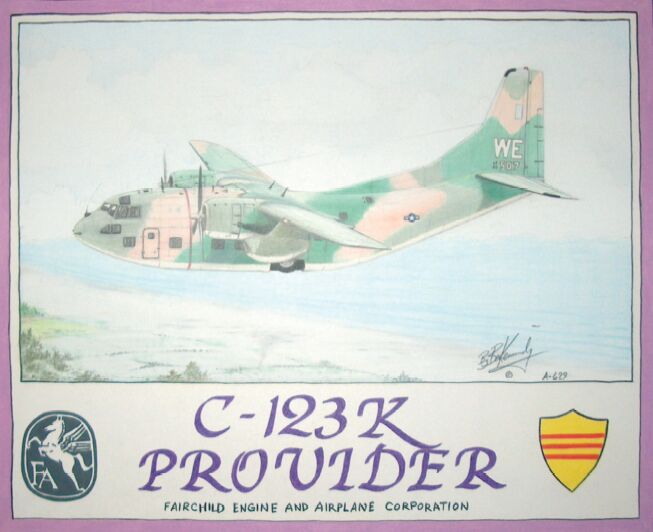

C-123K Provider

This C-123 is turning inbound over the coast, somewhere south of Chu Lai. His next turn will

be to the right as he sets up his approach to the runway at Chu Lai.

When flying across South Vietnam, air crews would go feet wet when practical. This

means they would take off, fly out over the South China Sea, follow the coast to a point near where

they were going, and then turn back over land, to make the approach to the air field they were

going to. An obvious reason was to avoid hostile ground fire, but a more practical reason was to

avoid our own artillery fire. If you flew over land, you had to stay in radio contact with Red Leg

(the artillery fire control center),

which gave you information about where any artillery fire in any certain area was coming from,

where it was going, and to what maximum elevation (or altitude) the cannon fire would reach.

You could then picture an arc from one point on the ground to another, and you had to avoid flying

through that arc. It took a lot of map work to avoid our own gun artillery, so if you had very far to

go up or down the coast, your life got much simpler if you just went feet wet.

|

|---|

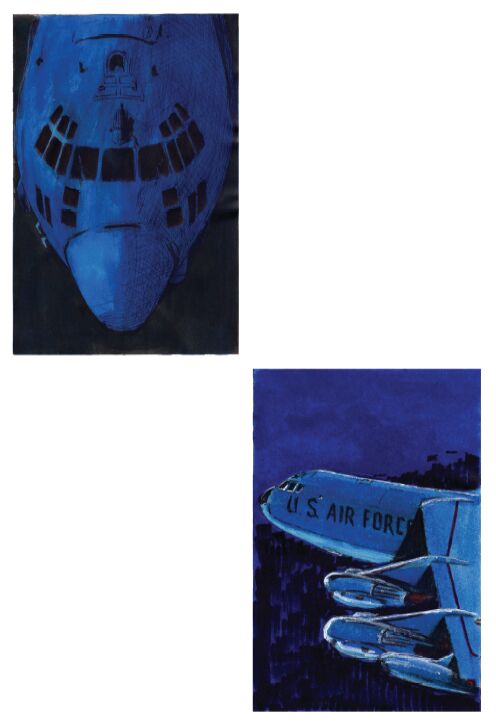

AC-130 (above, upper drawing)

The AC-130 gunship was an improved follow-on to the AC-47 Gunship. The AC-47 seemed

to prove the concept, and the AC-130 took it all to new levels of sophistication. This colored ink

drawing of the nose section of an AC-130 at night represents the dark and mysterious atmosphere

around the operations and missions of these deadly attack aircraft.

B-52 (above, lower drawing)

This is a colored ink drawing of a B-52 Bomber at night. The B-52 bombed targets all around Vietnam,

both in the north and the south, and could fly missions around the clock.

|

|---|

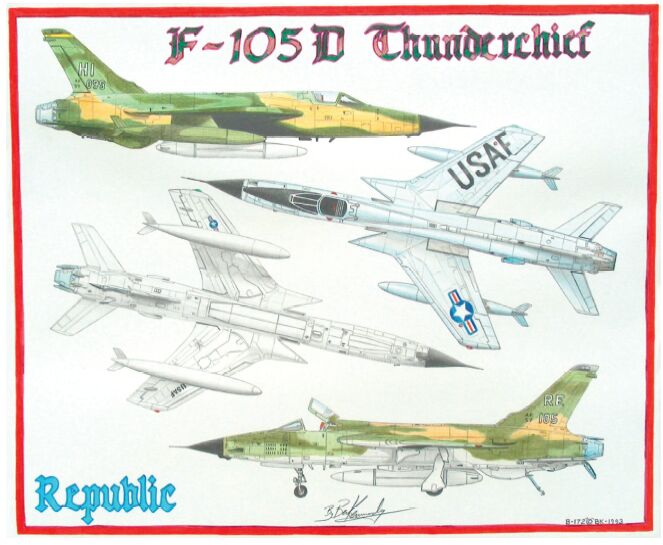

F-105D Thunderchief

The F-105 Thunderchief was used from early on in the war. Flown by the U.S. Air Force, it

was employed in the ground attack and electronic roles as well as other missions, such as Recon.

|

|---|

F-105D Thunderchief

This mixed media drawing of the F-105 is predominantly colored pencil, with ink accents.

|

|---|

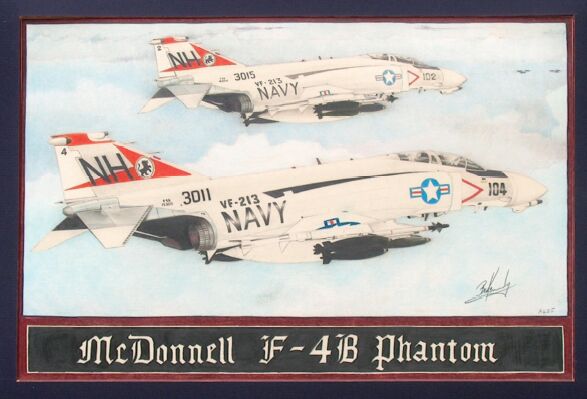

McDonnell F-4B Phantom

This colored Pencil Drawing of two F-4 Phantoms is done to represent the planes en route

to a target. This drawing is done without any ink, and makes use of the graphite pencil to a larger

degree than a mixed media work that would include inks. The colors in the wax based colored

pencil are very durable, and resist ultra-violet damage much better than the inks can. Pencil, and

colored pencil drawings can be as durable as the high quality oil paints.

|

|---|

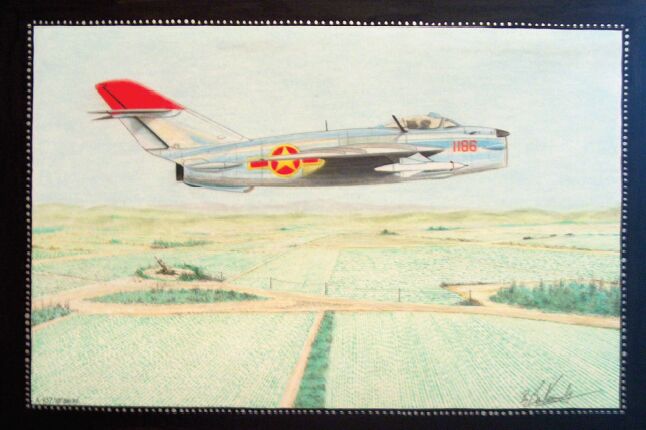

North Vietnamese MiG-17

The Soviet MiG-17 was a staple of the North Vietnamese Air Force. This colored pencil drawing

shows a MiG-17, low level, over Vietnam. A SAM missile site can be seen in the background, as the

MiG flies past.

This MiG-17 is on display at an Air Force museum in California. The North Vietnamese MiGs

were not allowed over South Vietnam, because we had complete air superiority over South Vietnam.

Any effort they may have made to fly over South Vietnam would have been fatal to them.

The only threat American aircraft had from the enemy, in the sky over South Vietnam, was enemy

ground fire. However, American flyers did engage the North Vietnamese fighter planes over the sky

of North Vietnam.

|

|---|

The North American F-86 Sabre

The F-86 Sabre Jet was used by some SEATO Forces in Vietnam, but this Korean War

veteran was getting old by the time the war expanded in Vietnam.

|

|---|

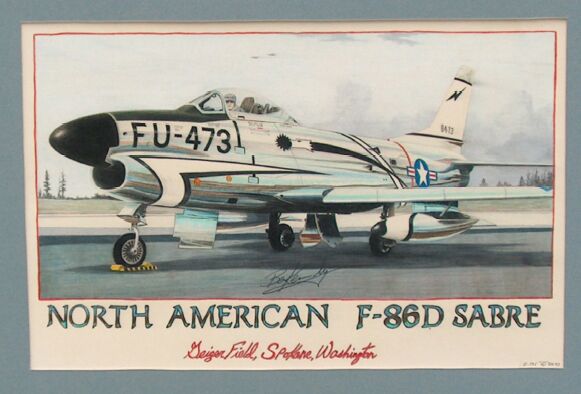

North American F-86D Sabre

This F-86D was assigned to the Air National Guard at Geiger Field, outside Spokane,

Washington. The Artwork is done in colored pencil. The Air National Guard no longer operates out

of Geiger Field, which has become the Spokane International Airport. Fairchild Air Force Base is

nearby, and military flights are conducted out of that SAC (Strategic Air Command) Base, as they

have been since the Vietnam War.

|

|---|

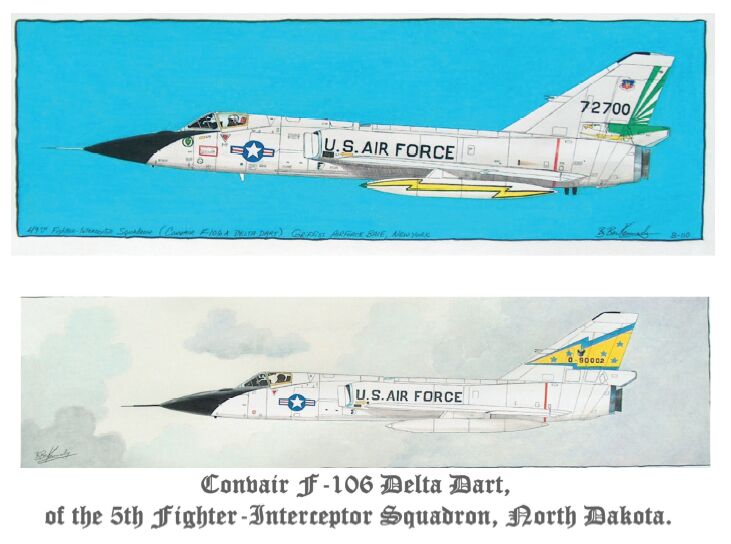

Convair F-106

Colored pencil drawings of the F-106 in Air Defense Command colors.

|

|---|

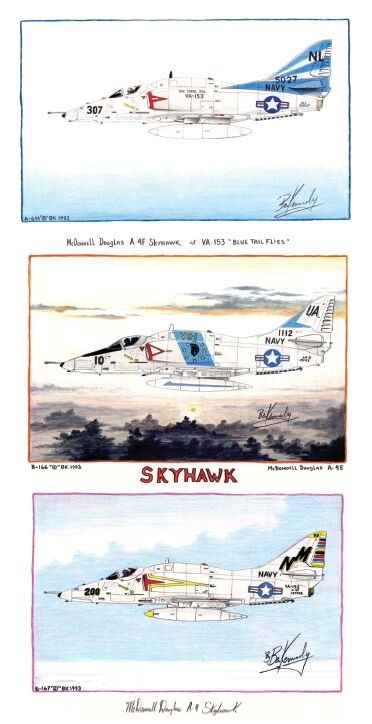

A-4 Skyhawk

Three mixed-media works, using colored ink and colored pencil, man's handiwork against a

backdrop of God's majesty.

|

|---|

AH-1S

The AH-1S is a Post Vietnam War Huey Cobra. It has sophisticated night fighting capability

developed by the Army in the years immediately following the Vietnam War. These drawings are

done with colored ink.

|

|---|

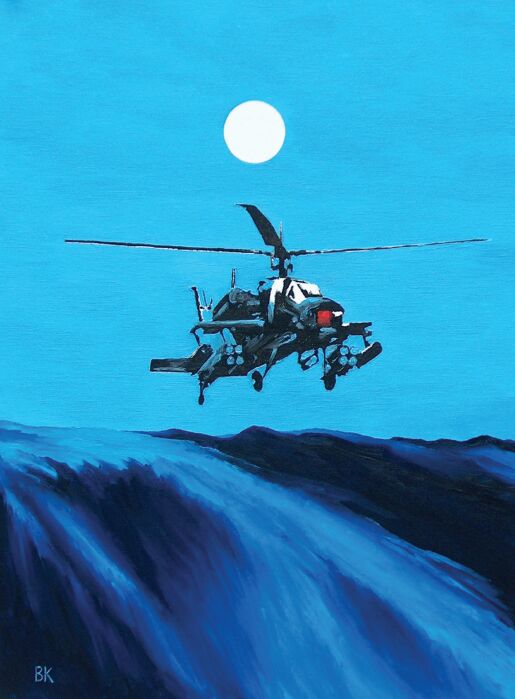

AH-64 APACHE

This 18 x 24 inch oil painting depicts the AH-64 Apache Helicopter at night. Incorporating

state of the art technologies developed from experience with the Vietnam era armed helicopters;

the Apache is an important part of the United States military's ability to exercise our force of will

to meet a variety of hostile challenges to our national interest.